Series Introduction

We will write a simple boot loader from scratch, using x86 assembly language and load a very minimal operating system kernel written in C. For the sake of simplicity we will utilize BIOS and not mess with UEFI.

The post is structured as follows. Before we jump into the details, it might make sense to look some things up in order to be able to follow my brief explanations. Consequently, the next sections contains some key words that you can read up on. Afterwards we are going to write our boot loader step by step. We then implement our minimalistic kernel written in C. In the last section we will wire everything together and boot our very own operating system.

The source code can be found at GitHub.

Prerequisites

In order to keep this post short I am going to focus on what is most important to achieve our goal. This means that some things will be left unexplained. However, if you spend some time to read up on them in more detail in the course of this post, you should be able to follow along just fine.

Here is a list of topics that are useful to know / to read up on in order to understand the content of this post.

- Basic understanding of computer architecture (CPU, memory, disk, BIOS)

- Basic understanding of how to interact with x86 CPUs (x86 architecture, x86 assembler)

- Basic understanding of how to compile a C program (make, gcc, ld)

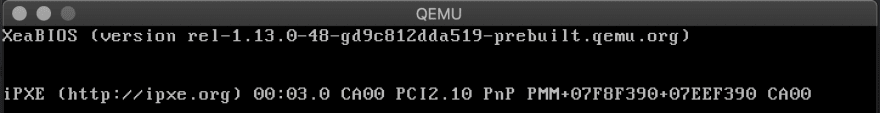

In terms of tooling we will need an emulator (QEMU) to run our operating system, an x86 assembler (NASM) to write our boot loader code, as well as a C compiler (gcc) and linker (ld) in order to create an executable operating system kernel. We will wire everything together using GNU Make.

Tasks of a Boot Loader

On an x86 machine, the BIOS selects a boot device, then copies the first sector from the device into physical memory at memory address 0x7C00. In our case this so called boot sector will hold 512 bytes. These 512 bytes contain the boot loader code, a partition table, the disk signature, as well as a "magic number" that is checked by the BIOS to avoid accidentally loading something that is not supposed to be a boot sector. The BIOS then instructs the CPU to jump to the beginning of the boot loader code, essentially passing control to the boot loader.

In this tutorial we will be only concerned about the boot loader code, which will start the operating system kernel. This is necessary because we will not be able to fit the whole operating system into 512 bytes. In order to start our kernel, the boot loader will have to perform the following tasks:

- Loading the kernel from disk into memory.

- Setting up the global descriptor table (GDT).

- Switching from 16 bit real mode to 32 bit protected mode and passing control to the kernel.

Organizing the Codebase

We are going to write the boot loader in x86 assembly using NASM. The kernel will be written in C. We will organize the code in multiple files to increase readability and modularity. The following files will be relevant for a minimal setup:

-

mbr.asmis the main file defining the master boot record (512 byte boot sector) -

disk.asmcontains code to read from disk using BIOS -

gdt.asmsets up the GDT -

switch-to-32bit.asmcontains code to switch to 32 bit protected mode -

kernel-entry.asmcontains assembler code to hand over to our main function inkernel.c -

kernel.ccontains the main function of the kernel -

Makefilewires the compiler, linker, assembler and emulator together so we can boot our operating system

The next section focuses on writing the boot loader related files (mbr.asm, disk.asm, gdt.asm, and switch-to-32bit.asm).

Afterwards we will write the kernel and the entry file. Finally, we are

going to write everything together and attempt to boot.

Writing the Boot Loader

Master Boot Record File

The main assembly file for the boot loader contains the definition of

the master boot record, as well as include statements for all relevant

helper modules. Let's first take a look at the file as a whole and then

discuss each section individually.

[bits 16]

[org 0x7c00]

; where to load the kernel to

KERNEL_OFFSET equ 0x1000

; BIOS sets boot drive in 'dl'; store for later use

mov [BOOT_DRIVE], dl

; setup stack

mov bp, 0x9000

mov sp, bp

call load_kernel

call switch_to_32bit

jmp $

%include "disk.asm"

%include "gdt.asm"

%include "switch-to-32bit.asm"

[bits 16]

load_kernel:

mov bx, KERNEL_OFFSET ; bx -> destination

mov dh, 2 ; dh -> num sectors

mov dl, [BOOT_DRIVE] ; dl -> disk

call disk_load

ret

[bits 32]

BEGIN_32BIT:

call KERNEL_OFFSET ; give control to the kernel

jmp $ ; loop in case kernel returns

; boot drive variable

BOOT_DRIVE db 0

; padding

times 510 - ($-$$) db 0

; magic number

dw 0xaa55

The first thing to notice is that we are going to switch between 16

bit real mode and 32 bit protected mode so we need to tell the assembler

whether it should generate 16 bit or 32 bit instructions. This can be

done by using the [bits 16] and [bits 32] directives,

respectively. We are starting off with 16 bit instructions as the BIOS

jumps to the boot loader while the CPU is still in 16 bit mode.

In NASM, the [org 0x7c00] directive sets the assembler location counter. We specify the memory address

where the BIOS is placing the boot loader. This is important when using

labels as they will have to be translated to memory addresses when we

generate machine code and those addresses need to have the correct

offset.

The KERNEL_OFFSET equ 0x1000 statement defines an assembler constant called KERNEL_OFFSET with the value 0x1000 which we will use later on when loading the kernel into memory and jumping to its entry point.

Preceding the boot loader invocation, the BIOS stores the selected boot drive in the dl register. We are storing this information in memory inside the BOOT_DRIVE variable so we can use the dl register for something else without the risk of overwriting this information.

Before we can call the kernel loading procedure, we need to setup the stack by setting the stack pointer registers sp (top of stack, grows downwards) and bp (bottom of stack). We will place the bottom of the stack in 0x9000

to make sure we are far away enough from our other boot loader related

memory to avoid collisions. The stack will be used, e.g., by the call and ret statements to keep track of memory addresses when executing assembly procedures.

Now the time has come to do some work! We will first call the load_kernel procedure to instruct the BIOS to load the kernel from disk into memory at the KERNEL_OFFSET address. load_kernel makes use of our disk_load procedure which we will write later. This procedure takes three input parameters:

- The memory location to place the read data into (

bx) - The number of sectors to read (

dh) - The disk to read from (

dl)

As soon as we are done we will return to the next instruction call switch_to_32bit,

which calls another helper procedure that we will write later. It will

prepare everything needed in order to switch to 32 bit protected mode,

perform the switch, and jump to the BEGIN_32BIT label when it is done, effectively passing control to the kernel.

This concludes our main boot loader code. In order to generate a

valid master boot record, we need to include some padding by filling up

the remaining space with 0 bytes times 510 - ($-$$) db 0 and the magic number dw 0xaa55.

Next, let's see how the disk_load procedure is defined so we can read our kernel from disk.

Reading from Disk

Reading from disk is rather easy when working in 16 bit mode, as we can utilize BIOS functionality by sending interrupts. Without the help of the BIOS we would have to interface with the I/O devices such as hard disks or floppy drives directly, making our boot loader way more complex.

In order to read data from disk, we need to specify where to start

reading, how much to read, and where to store the data in memory. We can

then send an interrupt signal (int 0x13) and the BIOS will do its work, reading the following parameters from the respective registers:

| Register | Parameter |

|---|---|

ah |

Mode (0x02 = read from disk) |

al |

Number of sectors to read |

ch |

Cylinder |

cl |

Sector |

dh |

Head |

dl |

Drive |

es:bx |

Memory address to load into (buffer address pointer) |

If there are disk errors, BIOS will set the carry bit. In that case we should usually show an error message to the user but since we did not cover how to print strings and we are not going to in this post, we will simply loop indefinitely.

Let's take a look at the contents of disk.asm now.

disk_load:

pusha

push dx

mov ah, 0x02 ; read mode

mov al, dh ; read dh number of sectors

mov cl, 0x02 ; start from sector 2

; (as sector 1 is our boot sector)

mov ch, 0x00 ; cylinder 0

mov dh, 0x00 ; head 0

; dl = drive number is set as input to disk_load

; es:bx = buffer pointer is set as input as well

int 0x13 ; BIOS interrupt

jc disk_error ; check carry bit for error

pop dx ; get back original number of sectors to read

cmp al, dh ; BIOS sets 'al' to the # of sectors actually read

; compare it to 'dh' and error out if they are !=

jne sectors_error

popa

ret

disk_error:

jmp disk_loop

sectors_error:

jmp disk_loop

disk_loop:

jmp $

The main part of this file is the disk_load procedure. Recall the input parameters we set in mbr.asm:

- The memory location to place the read data into (

bx) - The number of sectors to read (

dh) - The disk to read from (

dl)

First thing every procedure should do is to push all general purpose registers (ax, bx, cx, dx) to the stack using pusha so we can pop them back before returning in order to avoid side effects of the procedure.

Additionally we are pushing the number of sectors to read (which is stored in the high part of the the dx register) to the stack because we need to set dh

to the head number before sending the BIOS interrupt signal and we want

to compare the expected number of sectors read to the actual one

reported by BIOS to detect errors when we are done.

Now we can set all required input parameters in the respective registers and send the interrupt. Keep in mind that bx and dl

are already set correctly by the caller. As the goal is to read the

next sector on disk, right after the boot sector, we will read from the

boot drive starting at sector 2, cylinder 0, head 0.

After the int 0x13 has been executed, our kernel should

be loaded into memory. To make sure there were no problems, we should

check two things: First, whether there was a disk error (indicated by

the carry bit) using a conditional jump based on the carry bit jc disk_error. Second, whether the number of sectors read (set as a return value of the interrupt in al) matches the number of sectors we attempted to read (popped from stack into dh) using a comparison instruction cmp al, dh and a conditional jump in case they are not equal jne sectors_error.

In case something went wrong we will run into an infinite loop. If everything went fine, we are returning from the procedure back to the main function. The next task is to prepare the GDT so we can switch to 32 bit protected mode.

Global Descriptor Table (GDT)

As soon as we leave 16 bit real mode, memory segmentation works a bit differently. In protected mode, memory segments are defined by segment descriptors, which are part of the GDT.

For our boot loader we will setup the simplest possible GDT, which resembles a flat memory model. The code and the data segment are fully overlapping and spanning the complete 4 GB of addressable memory. Our GDT is structured as follows:

- A null segment descriptor (eight 0-bytes). This is required as a safety mechanism to catch errors where our code forgets to select a memory segment, thus yielding an invalid segment as the default one.

- The 4 GB code segment descriptor.

- The 4 GB data segment descriptor.

A segment descriptor is a data structure containing the following information:

- Base address: 32 bit starting memory address of the segment. This will be

0x0for both our segments. - Segment limit: 20 bit length of the segment. This will be

0xffffffor both our segments. - G (granularity): If set, the segment limit is counted as 4096-byte pages. This will be

1for both of our segments, transforming the limit of0xfffffpages into0xfffff000bytes = 4 GB. - D (default operand size) / B (big): If set, this is a 32 bit segment, otherwise 16 bit.

1for both of our segments. - L (long): If set, this is a 64-bit segment (and D must be

0).0in our case, since we are writing a 32 bit kernel. - AVL (available): Can be used for whatever we like (e.g. debugging) but we are just going to set it to

0. - P (present): A

0here basically disables the segment, preventing anyone from referencing it. Will be1for both of our segments obviously. - DPL (descriptor privilege level): Privilege level on the protection ring required to access this descriptor. Will be

0in both our segments, as the kernel is going to access those. - Type: If

1, this is a code segment descriptor. Set to0means it is a data segment. This is the only flag that differs between our code and data segment descriptors. For data segments, D is replaced by B, C is replaced by E and R is replaced by W. - C (conforming): Code in this segment may be called from less-privileged levels. We are setting this to

0to protect our kernel memory. - E (expand down): Whether the data segment expands from the limit down to the base. Only relevant for stack segments and set to

0in our case. - R (readable): Set if the code segment may be read from. Otherwise it can only be executed. Set to

1in our case. - W (writable): Set if the data segment may be written to. Otherwise it can only be read. Set to

1in our case. - A (accessed): This flag is set by the hardware when the segment is accessed, which can be useful for debugging.

Unfortunately the segment descriptor does not contain these values in a linear fashion but instead they are scattered across the data structure. This makes it a bit tedious to define the GDT in assembly. Please consult the diagram below for a visual representation of the data structure.

In addition to the GDT itself we also need to setup a GDT descriptor. The descriptor contains both the GDT location (memory address) as well as its size.

Enough theory, let's look at the code! Below you can find our gdt.asm,

containing the definition of the GDT descriptor and the two segment

descriptors, along with two assembly constants in order for us to know

where the code segment and the data segment are located inside of the

GDT.

;;; gdt_start and gdt_end labels are used to compute size

; null segment descriptor

gdt_start:

dq 0x0

; code segment descriptor

gdt_code:

dw 0xffff ; segment length, bits 0-15

dw 0x0 ; segment base, bits 0-15

db 0x0 ; segment base, bits 16-23

db 10011010b ; flags (8 bits)

db 11001111b ; flags (4 bits) + segment length, bits 16-19

db 0x0 ; segment base, bits 24-31

; data segment descriptor

gdt_data:

dw 0xffff ; segment length, bits 0-15

dw 0x0 ; segment base, bits 0-15

db 0x0 ; segment base, bits 16-23

db 10010010b ; flags (8 bits)

db 11001111b ; flags (4 bits) + segment length, bits 16-19

db 0x0 ; segment base, bits 24-31

gdt_end:

; GDT descriptor

gdt_descriptor:

dw gdt_end - gdt_start - 1 ; size (16 bit)

dd gdt_start ; address (32 bit)

CODE_SEG equ gdt_code - gdt_start

DATA_SEG equ gdt_data - gdt_start

With the GDT and the GDT descriptor in place, we can finally write the code that performs the switch to 32 bit protected mode.

Switching to Protected Mode

In order to switch to 32 bit protected mode so that we can hand over control to our 32 bit kernel, we have to perform the following steps:

- Disable interrupts using the

cliinstruction. - Load the GDT descriptor into the GDT register using the

lgdtinstruction. - Enable protected mode in the control register

cr0. - Far jump into our code segment using

jmp. This needs to be a far jump so it flushes the CPU pipeline, getting rid of any prefetched 16 bit instructions left in there. - Setup all segment registers (

ds,ss,es,fs,gs) to point to our single 4 GB data segment. - Setup a new stack by setting the 32 bit bottom pointer (

ebp) and stack pointer (esp). - Jump back to

mbr.asmand give control to the kernel by calling our 32 bit kernel entry procedure.

Now let's translate that into assembly so we can write switch-to-32bit.asm:

[bits 16]

switch_to_32bit:

cli ; 1. disable interrupts

lgdt [gdt_descriptor] ; 2. load GDT descriptor

mov eax, cr0

or eax, 0x1 ; 3. enable protected mode

mov cr0, eax

jmp CODE_SEG:init_32bit ; 4. far jump

[bits 32]

init_32bit:

mov ax, DATA_SEG ; 5. update segment registers

mov ds, ax

mov ss, ax

mov es, ax

mov fs, ax

mov gs, ax

mov ebp, 0x90000 ; 6. setup stack

mov esp, ebp

call BEGIN_32BIT ; 7. move back to mbr.asm

After switching the mode we are ready to hand over control to our kernel. Let's implement a dummy kernel in the next section.

Writing a Dummy Kernel

C Kernel

Having our basic boot loader functionality up and running we only need to create a small dummy kernel function in C that we can call from our boot loader. Although leaving the 16 bit real mode means we will not have the BIOS at our disposal anymore and we need to write our own I/O drivers, we now have the ability to write code in a higher order language like C! This means we do not have to rely on assembly language anymore.

For now the task of the kernel will be to output the letter X in the

top left corner of the screen. To do that we will have to modify video memory directly. For color displays with VGA text mode enabled the memory begins at 0xb8000.

Each character consists of 2 bytes: The first byte represents the

ASCII encoded character, the second byte contains color information.

Below is a simple main function inside kernel.c that prints an X in the top left corner of our screen.

void main() {

char* video_memory = (char*) 0xb8000;

*video_memory = 'X';

}

Kernel Entry

When you take a look back into our mbr.asm, you will

notice that we still need to call the main function written in C. To do

that, we are going to create a small assembly program that will be

placed at the KERNEL_OFFSET location, in front of the compiled C kernel when creating the boot image.

Let's look at the contents of kernel-entry.asm:

[bits 32]

[extern main]

call main

jmp $

As expected there is not much to do here. We only want to call our main function. To avoid errors in the assembly process, we need to declare main

as an external procedure that is not defined within our assembly file.

It is the task of the linker to resolve the memory address of main such that we can call it successfully.

It is important to remember that the kernel-entry.asm is not included into our mbr.asm

but will be placed at the front of the kernel binary in the course of

the next section. So let's see how we can combine all the pieces we

built.

Putting Everything Together

In order to built our operating system image we are going to need a bit of tooling. We need nasm to process our assembly files. We need gcc to compile our C code. We need ld to link our compiled kernel object files and our compiled kernel entry into a binary file. And we are going to use cat to combine our master boot record and our kernel binary into a single, bootable binary image.

But how do we wire all those neat little tools together? Luckily there is another tool for that: make. So here goes the Makefile:

# $@ = target file

# $< = first dependency

# $^ = all dependencies

# First rule is the one executed when no parameters are fed to the Makefile

all: run

kernel.bin: kernel-entry.o kernel.o

ld -m elf_i386 -o $@ -Ttext 0x1000 $^ --oformat binary

kernel-entry.o: kernel-entry.asm

nasm $< -f elf -o $@

kernel.o: kernel.c

gcc -m32 -ffreestanding -c $< -o $@

mbr.bin: mbr.asm

nasm $< -f bin -o $@

os-image.bin: mbr.bin kernel.bin

cat $^ > $@

run: os-image.bin

qemu-system-i386 -fda $<

clean:

$(RM) *.bin *.o *.dis

It is important to note that you might have to cross compile ld and gcc in order to be able to compile and link into free standing x86 machine code. I had to do it on my Mac at least.

Now let's compile, assemble, link, load our image into qemu, and look at the beautiful X in the top left corner of the screen!

Thanks to Read and Enjoy this Useful Knowledge.